Dogs (not) gone wild: DNA tests show most 'wild dogs' in Australia are pure dingoes

ItŌĆÖs time to take dingoes out of the doghouse.╠²

ItŌĆÖs time to take dingoes out of the doghouse.╠²

Almost all wild canines in Australia are genetically more than half dingo, a new study led by ╣·├±▓╩Ų▒ Sydney shows ŌĆō suggesting that lethal measures to control ŌĆświld dogŌĆÖ populations are primarily targeting dingoes.

The study, published today in , collates the results from over 5000 DNA samples of wild canines across the country, making it the largest and most comprehensive dingo data set to date.╠²

The team found that 99 per cent of wild canines tested were pure dingoes or dingo-dominant hybrids (that is, a hybrid canine with more than 50 per cent dingo genes).╠²

Of the remaining one per cent, roughly half were dog-dominant hybrids and the other half feral dogs.

ŌĆ£We donŌĆÖt have a feral dog problem in Australia,ŌĆØ says Dr , a conservation biologist from and lead author of the study. ŌĆ£They just arenŌĆÖt established in the wild.

ŌĆ£There are rare times when a dog might go bush, but it isnŌĆÖt contributing significantly to the dingo population.ŌĆØ

Pure dingoes with colourful coats are often mistaken for feral dogs. Photo: Michelle J Photography.

The study builds on a 2019 paper by the team that found . The newer paper looked at DNA samples from past studies across Australia, including more than 600 previously unpublished data samples.╠²

Pure dingoes ŌĆō dingoes with no detectable dog ancestry ŌĆō made up 64 per cent of the wild canines tested, while an additional 20 per cent were at least three-quarters dingo.

The findings challenge the view that pure dingoes are virtually extinct in the wild ŌĆō and call to question the widespread use of the term ŌĆświld dogŌĆÖ.

ŌĆ£ŌĆśWild dogŌĆÖ isnŌĆÖt a scientific term ŌĆō itŌĆÖs a euphemism,ŌĆØ says Dr Cairns.╠²

ŌĆ£Dingoes are a native Australian animal, and many people don't like the idea of using lethal control on native animals.

ŌĆ£The term ŌĆświld dogŌĆÖ is often used in government legislation when talking about lethal control of dingo populations.ŌĆØ┬Ā

The terminology used to refer to a species can influence our underlying attitudes about them, especially when it comes to native and culturally significant animals.╠²

This language can contribute to other misunderstandings about dingoes, like being able to judge a dingoŌĆÖs ancestry by the colour of its coat ŌĆō .

ŌĆ£There is an urgent need to stop using the term ŌĆświld dogŌĆÖ and go back to calling them dingoes,ŌĆØ says Mr Brad Nesbitt, an Adjunct Research Fellow at the University of New England and a co-author on the study.

ŌĆ£Only then can we have an open public discussion about finding a balance between dingo control and dingo conservation in the Australian bush.ŌĆØ

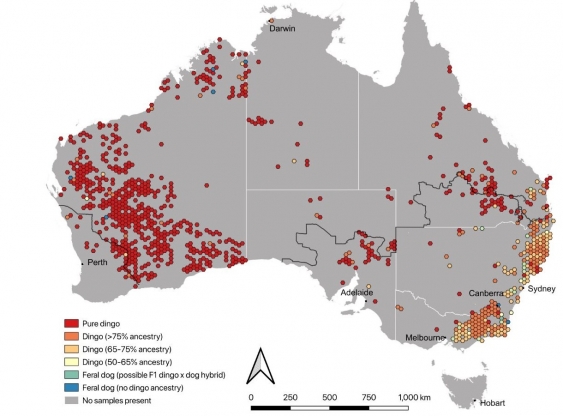

The median ancestry of wild canine DNA samples across Australia. Image: Cairns et al 2021.

While the study found dingo-dog hybridisation isnŌĆÖt widespread in Australia, it also identified areas across the country with higher traces of dog DNA than the national average.╠²

Most hybridisation is taking place in southeast Australia ŌĆō and particularly in areas that use long-term lethal control, like aerial baiting. This landscape-wide form of lethal control involves dropping meat baits filled with the pesticide sodium fluoroacetate (commonly known as 1080) into forests via helicopter or airplane.

ŌĆ£The pattern of hybridisation is really stark now that we have the whole country to look at,ŌĆØ says Dr Cairns.╠²

ŌĆ£Dingo populations are more stable and intact in areas that use less lethal control, like western and northern Australia. In fact, 98 per cent of the animals tested here are pure dingoes.

ŌĆ£But areas of the country that used long-term lethal control, like NSW, Victoria and southern Queensland, have higher rates of dog ancestry.ŌĆØ

The researchers suggest that higher human densities (and in turn, higher domestic dog populations) in southeast Australia are likely playing a key part in this hybridisation.

But the contributing role of aerial baiting ŌĆō which fractures the dingo pack structure and allows dogs to integrate into the breeding packs ŌĆō is something that can be addressed.

ŌĆ£If we're going to aerial bait the dingo population, we should be thinking more carefully about where and when we use this lethal control,ŌĆØ she says.

ŌĆ£Avoiding baiting in national parks, and during dingoesŌĆÖ annual breeding season, will help protect the population from future hybridisation.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Wild dogŌĆÖ isnŌĆÖt a scientific term ŌĆō itŌĆÖs a euphemism,ŌĆØ says Dr Cairns. Photo: Michelle J Photography.

Professor , senior author of the study and professor of conservation biology, has been researching dingoes and their interaction with the ecosystem for 25 years.╠²

He says they play an important role in maintaining the biodiversity and health of the ecosystem.

ŌĆ£As apex predators, dingoes play a fundamental role in shaping ecosystems by keeping number of herbivores and smaller predators in check,ŌĆØ says Prof. Letnic.╠²

ŌĆ£Apex predatorsŌĆÖ effects can trickle all the way through ecosystems and even extend to plants and soils.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Prof. LetnicŌĆÖs previous research has shown that suppressing dingo populations can lead to a growth in kangaroo numbers, which has repercussions for the rest of the ecosystem.

For example, high kangaroo populations can lead to overgrazing, which in turn ,╠² and can .╠²

A study published last month found the long-term impacts of these changes are so pronounced they are .╠²

But despite the valuable role they play in the ecosystem, dingoes are not being conserved across Australia ŌĆō unlike many other native species.

ŌĆ£Dingoes are a listed threatened species in Victoria, so theyŌĆÖre protected in national parks,ŌĆØ says Dr Cairns. ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖre not protected in NSW and many other states.ŌĆØ

Ditching the term 'wild dog' is the first step in starting meaningful conversations about balancing dingo management with conservation. Photo: Chontelle Burns / Nouveau Rise Photography.

Dr Cairns, who is also a scientific advisor to the , says the timing of this paper is important.

ŌĆ£There is a large amount of funding currently going towards aerial baiting inside national parks,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£This funding is to aid bushfire recovery, but aerial wild dog baiting doesnŌĆÖt target invasive animals or ŌĆświld dogsŌĆÖ ŌĆō it targets dingoes.╠²

ŌĆ£We need to have a discussion about whether killing a native animal ŌĆō which has been shown to have benefits for the ecosystem ŌĆō is the best way to go about ecosystem recovery.ŌĆØ

Dingoes are known to negatively impact farming by preying on livestock, especially sheep.

The researchers say itŌĆÖs important that these impacts are minimised, but how we manage these issues is deserving of wider consultation ŌĆō including discussing non-lethal methods to protect livestock.

ŌĆ£There needs to be a public consultation about how we balance dingo management and conservation,ŌĆØ says Dr Cairns. ŌĆ£The first step in having these clear and meaningful conversations is to start calling dingoes what they are.

ŌĆ£The animals are dingoes or predominantly dingo, and there are virtually no feral dogs, so it makes no sense to use the term ŌĆświld dogŌĆÖ. ItŌĆÖs time to call a spade a spade and a dingo a dingo.